Photograph from Northfield Echoes, Volume 1, A Report of the Northfield Conferences for 1894, D.L. Pierson, ed., E. Northfield, MA, The Conference Bookstore, 1894, p. 360

Photograph from Northfield Echoes, Volume 1, A Report of the Northfield Conferences for 1894, D.L. Pierson, ed., E. Northfield, MA, The Conference Bookstore, 1894, p. 360

Last month, on October 23, 2018, I attended a Moody Center event held on the grounds of the former Northfield Seminary for Young Ladies, a school founded in 1879 by famed Christian evangelist D.L. Moody, who was born (1837) and raised in the village of Northfield, Massachusetts. The Northfield Seminary was founded specifically to serve girls from poor families who had limited access to education. In time, the school developed a reputation as an excellent academic institution, and it began accepting students from all socioeconomic classes. Two years later (1881), the Mount Hermon School for Boys was established on the other side of the Connecticut River in Gill, MA, the current site of the consolidated Northfield-Mount Hermon (NMH).

The majority of the buildings and some acreage now belong to Thomas Aquinas College, a Roman Catholic, California-based liberal arts college that plans to open an East Coast campus there in 2019. Plans call for it to eventually serve 350 to 400 students. Some additional acreage and 10 other buildings are now owned by the aforementioned Moody Center, a nonprofit organization honoring the legacy of NMH founder D.L. Moody.

The Auditorium, Northfield Seminary, circa 1904, built 1894. Detroit Publishing Co., from the Library of Congress collection

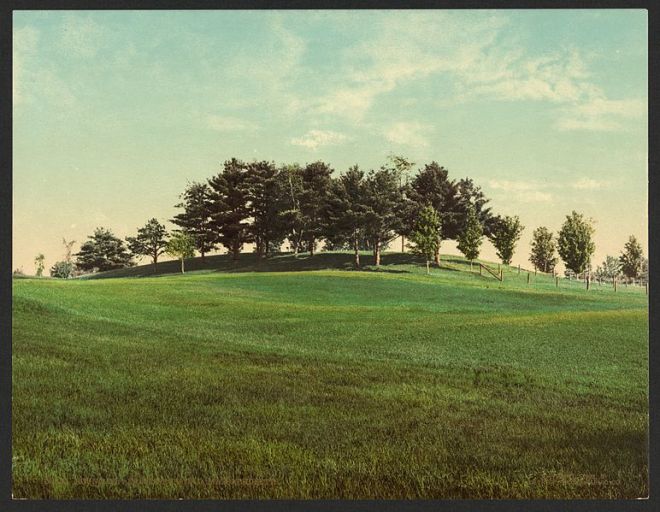

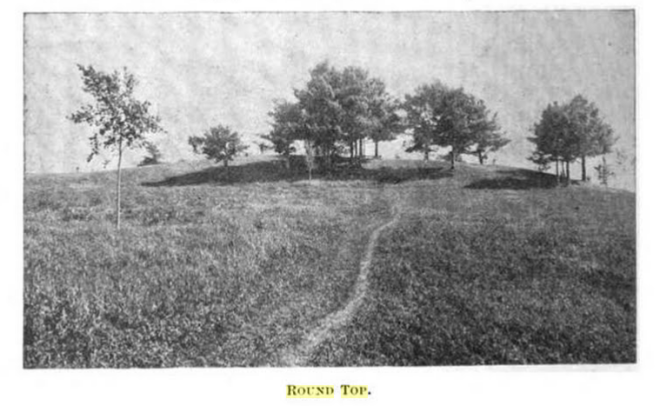

The event was styled the official public launch of the Moody Center and an announcement of its plans for the future at the campus. It was held in the Auditorium, built in 1894 with a capacity of 2500 people, and situated on a height of land at the easterly edge of the grounds. Thousands of classes, conferences, concerts, and church services have been held inside this imposing edifice in its 125 years. Conducted as a joint public announcement and evangelical Christian service, the October 23rd event was to include a rededication of the gravesite of Dwight Moody (died 1899) and his wife, Emma Revell Moody (died 1903), situated on a small knoll known as Round Top, immediately to the south of the Auditorium. Round Top, often referred to as “the most hallowed place in Northfield,” figured largely in the life story of Moody and the many others that have gathered at the school over the years to join in the various religious and educational activities there. A search online makes its significance in this regard abundantly clear.

A contemporary view of the Dwight and Emma Moody gravesite at Round Top, ali nkihl8t, looking westward (Western Abenaki).

“Round Top,” wrote J. Wilbur Chapman, “has ever been a place of blessing. . . . Each evening, when the conferences are in session, as the day is dying out of the sky . . . students gather to talk of the things concerning the Kingdom. . . . The old haystack at Williamstown figures no more conspicuously in the history of missions than Round Top figures in the lives of a countless number of Christians throughout the whole world.” source

More on that “old haystack at Williamstown” in a bit…

Back to the event: the program was structured in two parts, the first a worship service, some history to preface the announcement of the launch, an explanation of future plans, a recognition award, and then an intermission. The second part was to include additional worship, a keynote address, and then dismissal to nearby Round Top for the rededication ceremony. I sat in one of the many seats in an audience of scores of supporters and the curious public, for the first hour and a half, and then stepped outside at the break.

Thinking I had probably absorbed enough and would head back north toward home, I walked over to the gravesite knoll, where a photographer was setting up for the imminent rededication. I had in mind (even before I came there that day) the aphorism that disparate cultures may find the same geographical sites notable, and even sacred, and that Round Top may have been a significant location to the indigenous Sokoki, for any number of reasons within their own cultural values. There is often a pattern of displacement and replacement – intentional appropriation, both symbolic and physically – overlaid on these places, a site-specific instance of the land dispossession that defines colonization. For more, see Jean O’Brien’s excellent analysis of the wholesale application of this practice in Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England.

Round Top postcard, circa 1902, Detroit Publishing Co.

A light precipitation had begun to fall from the darkening sky and the breeze was picking up, as I approached the small prominence. The twin gray granite gravestones stood on the rise, surrounded by an iron chain with ornate posts, and sheltered by a small grove of tall white pines and stately white birches. I took in the open prospect before my eyes, looking up and down the valley of the Kwenitekw/Connecticut River, the wolhanak/intervale meadows, and the hills rolling off into the west, toward the Pocumtuk, Mount Greylock, and the Green Mountains on the horizon, where the sun would end its traverse shortly.

The gentle mound of earth, at the height of land rising from the terraces, did indeed seem like a natural gathering place. In sight were Pachaug Meadow to the northwest, Great Meadow below, Natanis southwest at Bennett Meadow, and Moose Plain, across the River. The Great River Road following the east bank at the bottom of the immediate slope has now become Massachusetts Route 63. Thinking back to what this place may have looked like several hundred years ago, before Puritan captive Mary Rowlandson made her slow way northward past this very spot in 1676, I could picture fertile planting fields, grasslands regularly cleared with controlled burns, and wigwams on the higher ground around me. The scattered raindrops began to get larger and more frequent. I laid tobacco at the base of a twin birch, said good-bye to the photographer, wishing him well with the weather, and walked back to my car.

Since then, I hadn’t thought much more of it. But this week, I received by email a Moody Center newsletter, authored by Board Member Dr. Edwin Lutzer describing his participation as the keynote speaker during the October program. The newsletter is entitled “Standing Where D.L. Moody Stood – and Reviving His Legacy.” Several excerpts stood out as unexpected anomalies within an otherwise didactic and altogether familiar narrative (familiar because I grew up immersed in evangelical, fundamentalist Protestant Christianity, replete with plentiful references to D.L. Moody).

Here are the excerpts from Rev. Dr. Edwin Lutzer that caught me by surprise (or not…):

My keynote address was given in the original auditorium, built in 1894, while standing where D.L. Moody often stood to preach and where his funeral service was held in 1899. I began with a question — “Can these dry bones live?”…

After my message, the plan was for me to lead our 200+ guests to a nearby hill on the property known as “Round Top,” which is where D.L. Moody and his wife, Emma, are buried. In Moody’s day, this was referred to as the “Olivet” of the region, because Moody himself liked to gather students in the nearby valley and teach them the Scriptures. He even said he would like to be buried at the picturesque Round Top. Thankfully, his wishes were honored.

In the many decades since D.L. Moody’s death, students have continued to gather at Round Top for times of visiting and religious services. Word also has it that witches came to the property, representing their religion. Another board member shared that, as he walked up the hill many years ago, he saw what appeared to be a witch at Moody’s grave. She was dressed in all black and was chanting until she saw someone approaching and began to run. This is why a brief ceremony was planned for Round Top as part of the launch event, thus renouncing the past and rededicating the property to Jesus Christ and the furtherance of the Gospel.

Then it gets even more interesting:

Near the end of my address, I could hear the rumbling of thunder and wind was blowing rain against the outer windows of the auditorium. For the safety of our guests, a decision was made to keep the ten-minute rededication ceremony in the auditorium instead of proceeding to Round Top. After leading everyone in a final prayer of commitment, I opened my eyes and saw sunlight streaming through the windows…

As the service concluded and music filled the auditorium, guests began to leave and were immediately greeted with a double rainbow. Not only was the sun shining — but there was not a cloud in the sky! Some interpreted this as a sign of God’s blessing. He speaks through the thunder (see II Samuel 22:14; Psalm 77:17); but after the thunder comes the blessing of sunshine.

A thunderstorm sweeps over the Valley: Thomas Cole, The Oxbow (The Connecticut River near Northampton 1836).

I will end this interesting juxtaposition with several circumstantial observations:

- The ability of medeoulin or mdawinno (an Abenaki medicine person) – or pauwau, further south in Algonquian New England – to understand and work with the atmospheric spirit forces, among many others, was and is well-known.

- The powers of the Bad8giak, or the Thunders, who come from the west, are – in Abenaki cosmology – a natural positive counterbalance to other spirit powers considered more destructive or debilitating. They may be represented in the shape of a thunderbird and invoked to keep other energies at bay.

- Native medicine people were typically equated with witchcraft or sorcery by the early colonists; it is worth noting is that this characterization of association with evil persists in modern Christianity.

- The aforementioned “old haystack at Williamstown” is a reference to another noted moment in the Western Massachusetts evangelical timeline, this region having been a hotbed for Revivalism. At Williams College, founded through a bequest of Col. Ephraim Williams, Jr. – a relative of Northampton’s Rev. Jonathan Edwards of “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” fame and Rev. John Williams of the Deerfield Raid of 1704 – there was an August, 1806 event known as the Haystack Prayer Meeting. It is considered “the seminal event for the development of American Protestant missions in the subsequent decades and century.” Interestingly, a thunderstorm and grove of trees figures prominently in this account as well. From the Wiki article: “Williams College students Samuel Mills, James Richards, Francis LeBaron Robbins, Harvey Loomis, and Byram Green, met in the summer of 1806 in a grove of trees near the Hoosic River, in what was then known as Sloan’s Meadow, and debated the theology of missionary service. Their meeting was interrupted by a thunderstorm and the students took shelter under a haystack until the sky cleared. “The brevity of the shower, the strangeness of the place of refuge, and the peculiarity of their topic of prayer and conference all took hold of their imaginations and their memories.”

- And, oddly enough, in D.L. Moody’s own genealogy can be found one of the targets of the colonial Connecticut witch trials, contemporaneous with the better-known episodes in Salem, MA. Elizabeth (Moody) Seager/Seger (1628-1666) of Hartford was accused and tried three times for witchcraft, and convicted in the last instance (1665), although the charges were dismissed the next year and she was set free. Robert Stern, one of those testifying against Elizabeth, stated: “I saw This woman Goodwife Seage/ in the woods w[i]th three more wome[n]/ and wit[h] them {these} I saw two/ black creatures like two Indians/ but taller I saw likewise a Kettle/ there over a fire, I saw the wome[n]/ dance round these black Creatures/ and whiles I looked upon them one/ of the women G Greensmith sai[th]/ look who is yonder and then they/ ran away up the hill. “

Note: this is an anecdotal observation of a place-based intersection of spiritualities in Squakheag/Northfield, a center of Sokwakiak culture. Food for thought.